Frances Jane Baptiste was the daughter of a dancing master (said to be a native Frenchman) who had gone into her father’s trade as a teacher herself.

Frances had met William Cotgrave – also a dance teacher – when the her father had joined forces with him in a partnership in Chester.

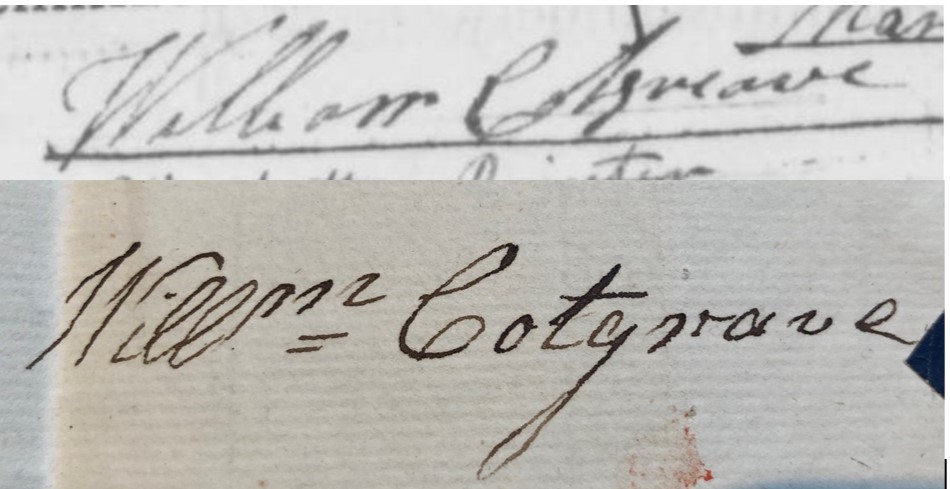

William – who seems never to have been sure how to spell his own surname – had died in 1820 leaving her with a small child and a financial inheritance that was not trivial but was hardly great riches.

Frances and her young son then lived in Warrington until she died seven years later, whereupon her testamentary bequests started a wholly unnecessary row.

George Furnival, who had his own business as a “carrier,” engaged in transporting heavy goods and commodities, appears to have been Frances’s landlord – at any rate he was the owner of property in and around her home. A few weeks after her death, he made the twenty mile journey from Warrington to Chester (perhaps he had to go anyway as part of his haulage business), where he turned up in person at the consistory court offices to lodge a complaint. He alleged that a lawyer called James Bayley was thwarting his attempts to administer Mrs Cotgrave’s estate. Bayley, according to Furnival’s claim, was sitting on the woman’s will and refusing to hand it over to the people she had specified as her executors. George Furnival knew that he was named as one of those executors, and all he he wanted to do was get on with the job of settling Mrs Cotgrave’s affairs. It is not clear whether he knew the details of what the will actually said, but it would not have been hard to guess because Frances Cotgrave was a widow with just the one child, a 14-year old son called Jonathan. So her instructions were simple: sell everything she owned, put the money into safe, government-backed investments, and use the interest to support Jonathan until he was 21, when he would inherit the capital. In the meantime, the executors were to use their discretion in enrolling the teenager to learn a trade so that he would be able to make a decent living to supplement the modest income his investments would provide. But without the legal authority of an order from the probate court, the executors could not liquidate any assets or spend or invest any of Mrs Cotgrave’s money and the teenager was presumably living off the kindness of friends, relatives and neighbours, or running up credit secured against his inheritance.

Bayley was summoned by the court to explain why he was clinging to the will, and when he turned up in Chester on 5 March 1828, his story was slightly different. It was true, he said, that he was Mrs Cotgrave’s lawyer and had her last will and testament. It was also true that George Furnival was named as an executor, along with two other men. But before Frances’s death, all three had said they would refuse to act, even though according to Bayley, he had repeatedly sought to get them to pledge their involvement. Furnival specifically had said he wanted “nothing whatever to do with the said will or the affairs of the deceased”. As a result, claimed James Bayley, Frances Cotgrave had asked him to make a new version of her will, nominating a different executor. Somewhat conveniently, Bayley claimed that it was he himself whom she had asked to be the replacement executor. Bayley’s story was clearly fishy especially since he was the only person to believe it- whatever had been said in the past, Furnival was certainly not refusing to act now. But even if there was some truth in it, he had no right to withhold the original will and there was certainly nothing he could do about it now. Whatever Frances Cotgrave may have wanted when she was alive, she could hardly sign an updated document now she was dead.

The other two executors nominated in the will were relatives of Frances’s husband – his brother Dr Jonathan Cotgrave, a retired army surgeon who lived in Oxfordshire, and his cousin William Worthington whose home was about half way between Warrington and Chester. In the end, neither took on the role, so maybe it was true they had told Bayley they were reluctant, but it seems extremely unlikely that either would have point blank refused when the entire future of the 14-year old Jonathan Cotgrave (who had after all been named after his medical uncle) depended on it.

Bayley was made to hand over the document, Furnival took the necessary legally-binding oath and the probate court swiftly granted the necessary authority. George Furnival then presumably got on with the job. As it happens, the young Jonathan Cotgrave did not live all that long to enjoy his inheritance; he died in 1833 at the age of 20, so he never made it to his 21st birthday when he would have inherited control of the money his mother had left him. By then, most of his more immediate family had died and the estate went to his aunt Susannah Ollivant, who lived with her husband on the Isle of Man. And when she died a few years later in 1840, she passed on the income on investments to her brother Jonathan, the army medic who had originally been named in Frances Cotgrave’s will as “my worthy friend doctor Cotgrave”.

Sources

Lancashire Record Office WCW: Frances Cotgrave 1828

Chester Chronicle 26 January 1810; 31 July 1812

Deeds in private hands

Parish Registers

Cheshire Archives: DWW1/120